Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of VladTV. To submit your own article click here.

One thing that’s fascinating about hip hop is that it has a special elusiveness that other musical genres don’t. It resists all attempts to get boxed in. It’s unpredictable and dynamic. Other genres have this too, to some extent, but hip hop goes beyond just merely being reflective of the times. Hip hop can reflect current trends and then also turn around and say “you know what? Scrap whatever you got going on; this new stuff is what’s going to be hot right now.” And when hip hop speaks to its own community, even pop culture listens.

We’ve seen it when Run DMC stormed the scene during the ‘party era’ that stretched from the 70s and early 80s. We’ve seen it when West Coast gangster rap clashed with the experimental and creative early 90s. We’ve seen it with 50 Cent during Ja Rule’s short-lived but financially successful stint with the ‘sexy thug’ hip hop niche. While these are obviously generalizations and trends (not clear-cut consecutive eras), they show that rappers who seemingly had hip hop’s blessings can easily get their top tier popularity pass revoked by artists belonging to one of hip hop’s previously latent or subordinate undercurrents, without prior notice.

And hip hop doesn’t show favoritism. During Common’s 1994 hit "I Used to Love Her" it looked like she had her eyes set on gangster rap and was permanently pivoting away from alternative rap. We now know, in 2016, that she’ll flip the script and turn the table on anyone. Alternative rappers, hardcore rappers, gangster rappers, pop rappers and the ones who deserve it most: the powers that be who try to exploit, manipulate and formularize hip hop for their own gains.

This volatile nature of hip hop makes it a rewarding playground for strategists and those with strategic hunches in the industry. Rappers and industry insiders with a lucky hunch or talent for what worked in the hip hop climate in which they operated, like 50 Cent, 2Pac, MC Hammer, Russell Simmons (with Run DMC), Jam Master Jay (with Onyx), Irv Gotti (with Ja Rule), Dre (with Eminem), Trackmasters (with 50 Cent), etc. came up with winning strategies and got success quickly. As far as hip hop goes, however, not all strategic approaches are accepted within the community.

The most well received of these strategies meet three requirements. They fit: 1) the personalities, biographies and beliefs of the artists, 2) a niche within hip hop which is respected (e.g. conscious rap) and 3) the code of conduct of hip hop’s golden era (e.g. toughness and writing your own rhymes). The strategies that have historically done particularly well in the hip hop community don’t compromise on either of these three pillars of hip hop legitimacy and are typically rewarded with exponential success. In my view, rappers like DMX and 2Pac had strategies that belong to this orthodox camp.

Other strategies, advanced by rappers in what can be called the unorthodox camp, often met the requirement of entering one of the respected hip hop niches, but their strategies were often (perceived to be) contrived or subversive. This violated the remaining pillars of hip hop authenticity. Like the eternal dichotomy of Yin and Yang in nature, orthodox artists and fans who subscribe to all three pillars are in constant opposition with unorthodox artists and fans who dismiss one, two or even all three of these pillars.

But now something big is happening, which is alarming to orthodox fans and artists, but interesting from a strategic point of view, as it has huge strategic implications. One of these implications being the flow of more leverage and influence to corporate record labels and other players which have always wanted to push potentially highly lucrative unorthodox hip hop acts, but couldn’t do so without the approval of the hip hop community.

For instance, there are interests out there that would love to push gay rappers and tap into new markets if they could get away with it. But, right or wrong, hip hop has self-policing mechanisms that can restore the genre to any desired previous point, ridding it of unwanted directions and outside meddling. This has kept hip hop free from mass appropriation. It has also forced corporations to always come back to the people on the ground for new talent.

Now, for the first time, we can see that the rapid increase of the popularity and sheer numbers of unorthodox fans and artists is influencing hip hop affairs. This happens because of two reasons. First, with their influence waning, many orthodox rappers and fans seem to have started to look the other way. Secondly, these unorthodox fans and artists are supporting each other, effectively sidelining the need for a whole lot of orthodox hip hop fans. Aside from their traditional roles as power brokers, the orthodox camp isn’t exactly making their stamp of approval indispensable and desired in the eyes of unorthodox artists either, as they’re not the ones who are primarily buying hip hop records.

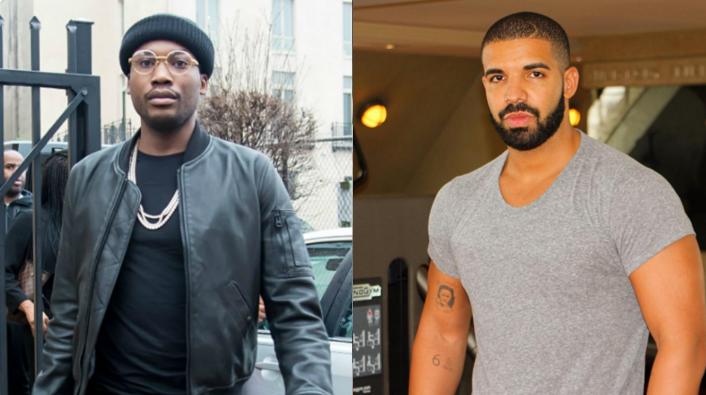

Meek’s recent clash with Drake and his inability to mobilize hip hop to his side, if not for abandoning Drake, then at least for riding with him on the ‘ghostwriting’ allegation, is partly symptomatic of the strategic shifts I’ve just described. And by saying this I’m not picking Meek’s side. It’s just that Meek was appealing directly to the orthodox hip hop community by invoking hip hop code of conduct that Drake allegedly violated, but, as far as that appeal goes, there was an ear-deafening silence on the other side. Meek couldn’t pull it off, and his misadventure of going against Drake, as well as what seems to be his lack of strategic insight, are costing him fans and the willingness of the public to give him a fair shake.

Other rappers on the sidelines who often silently agree with Meek in principle on the ghostwriting allegations are now looking at this and wondering what the implications are going to be if they speak up. This may be an unwarranted fear, as Meek dropped the ball on several occasions. So it’s not clear to what extent he is being punished for negligence as opposed to going against Drake.

On the other hand, it’s also not clear to me, to what extent Drake’s response has contributed to Meek’s predicament. But as far as public perception goes, the damage is already done. Many orthodox hip hop heads are looking at this situation thinking that going against prominent unorthodox rappers could be bad for their career. Unorthodox rappers may now become emboldened and feel validated by their violations of golden age hip hop code of conduct.